####### Video #######

Sometimes a simple photograph can stir unexpected emotions. Images captured across time often reveal unsettling stories hidden behind their surfaces. These haunting historical photos from the past challenge us to explore history’s darker moments and the lasting impact they leave behind.

Mountain of Bison Skulls (1892)

100vw, 787px” /></p>

<div class=)

In 1892, outside Michigan Carbon Works in Rougeville, Michigan, a staggering sight was captured: a towering mountain of bison skulls. These bones were destined to become fertilizer, glue, and charcoal, a chilling testament to the devastation wrought by colonization and industrial greed.

In the early 1800s, there were between 30 to 60 million bison in North America. By the time of this photo, fewer than 500 remained. Settlers’ expansion and the market’s thirst for bison products led to a brutal near-eradication, severing Indigenous people’s deep connection to the animals.

Today, wild bison have rebounded to around 31,000, but this photo remains a stark reminder of how close we came to losing them forever.

Inger Jacobsen and Jackie Bülow (1954)

100vw, 2045px” /></p>

<div class=)

At first glance, this 1950s photo feels unsettling, but it simply shows Norwegian singer Inger Jacobsen with her husband, ventriloquist Jackie Bülow.

Jacobsen was a celebrated artist who later represented Norway in Eurovision 1962, while Bülow captivated audiences with his ventriloquism skills during the golden age of radio and early television.

Though ventriloquism is less common today, talents like Terry Fator and Darci Lynne prove it still enchants audiences, keeping the art form alive.

The Sleeping Mummy Trader (1875)

100vw, 1086px” /></p>

<p><span data-preserver-spaces=) This 1875 image shows a trader sleeping among Egyptian mummies, a haunting glimpse into the strange exploitation of ancient relics.

This 1875 image shows a trader sleeping among Egyptian mummies, a haunting glimpse into the strange exploitation of ancient relics.

For centuries, Europeans treated mummies as commodities, grinding them into medicine, using them as fuel, or hosting macabre “unwrapping parties.”

The photograph highlights how grave robbing fueled an international mummy trade, turning cultural treasures into objects of curiosity and misuse, a practice we now view with deep regret.

Iron Lungs and the Fight Against Polio (1953)

100vw, 893px” /></p>

<div class=)

Rows of iron lungs, mechanical respirators that kept paralyzed children alive, tell a tragic story from the 1950s polio epidemic.

In 1952 alone, nearly 58,000 Americans contracted polio; thousands were left disabled or died, mainly children.

The sight of these giant machines is a chilling reminder of a time before vaccines, when survival often meant life inside a steel cylinder, dependent on machinery to breathe.

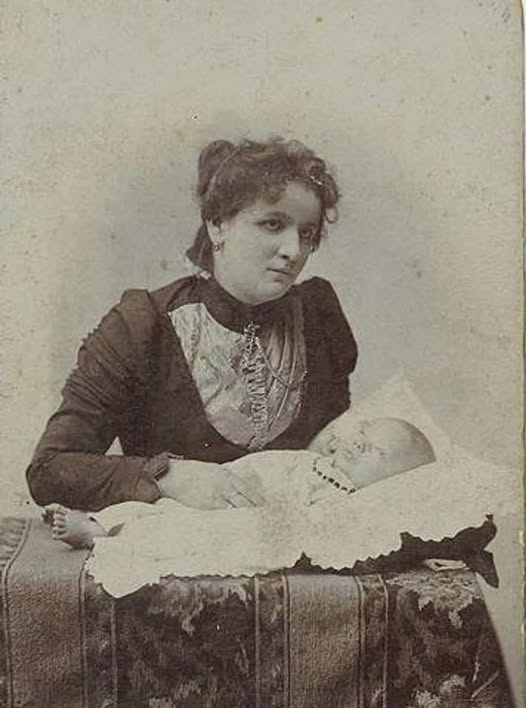

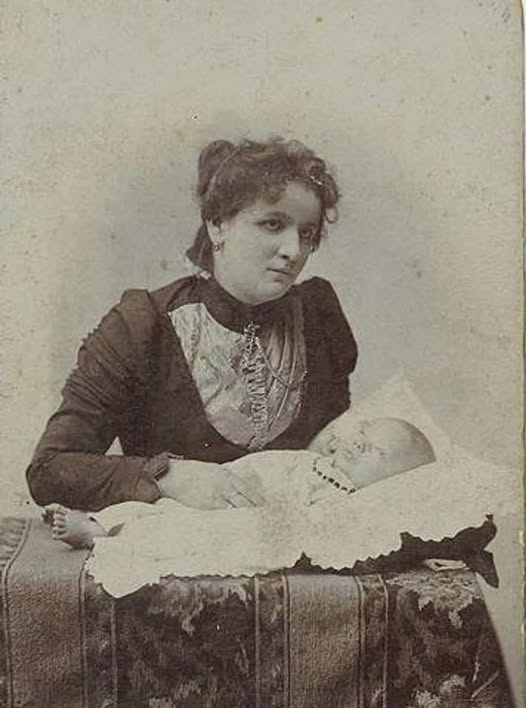

A Young Mother and Her Deceased Baby (1901)

100vw, 608px” /></p>

<div class=)

This heartbreaking photograph captures Otylia Januszewska holding her deceased son, Aleksander, a powerful example of Victorian post-mortem photography.

Rooted in the concept of memento mori (“remember you must die”), the practice helped grieving families honor and preserve the memory of their loved ones.

Though death is more hidden in today’s culture, Victorians faced it head-on, immortalizing loss through photographs that kept connections alive beyond the grave.

9-Year-Old Factory Worker in Maine (1911)

100vw, 1170px” /></p>

<div class=)

In 1911, 9-year-old Nan de Gallant spent her summer working in Maine’s Seacoast Canning Company instead of playing outdoors.

Child labor was widespread in early 20th-century America, with laws often full of loopholes that left kids vulnerable.

Nan’s story reflects a broader struggle: entire generations of children forced to trade their childhoods for survival, in an era when every working hand mattered.

James Brock Pours Acid Into a Pool (1964)

100vw, 676px” /></p>

<p><span data-preserver-spaces=) During a 1964 civil rights protest in St. Augustine, Florida, motel manager James Brock poured acid into a swimming pool to drive away Black activists.

During a 1964 civil rights protest in St. Augustine, Florida, motel manager James Brock poured acid into a swimming pool to drive away Black activists.

Captured by photographer Charles Moore, this horrifying act exposed the vicious racism activists faced during the fight for equality.

The photo stands today as both a painful reminder of hatred and a tribute to the bravery of those who refused to be pushed out.

Coal Miners Returning from the Depths (c.1900)

100vw, 1287px” /></p>

<div class=)

Advertisement

100vw, 787px” /></p>

<div class=)

100vw, 2045px” /></p>

<div class=)

100vw, 1086px” /></p>

<p><span data-preserver-spaces=) This 1875 image shows a trader sleeping among Egyptian mummies, a haunting glimpse into the strange exploitation of ancient relics.

This 1875 image shows a trader sleeping among Egyptian mummies, a haunting glimpse into the strange exploitation of ancient relics. 100vw, 893px” /></p>

<div class=)

100vw, 608px” /></p>

<div class=)

100vw, 1170px” /></p>

<div class=)

100vw, 676px” /></p>

<p><span data-preserver-spaces=) During a 1964 civil rights protest in St. Augustine, Florida, motel manager James Brock poured acid into a swimming pool to drive away Black activists.

During a 1964 civil rights protest in St. Augustine, Florida, motel manager James Brock poured acid into a swimming pool to drive away Black activists. 100vw, 1287px” /></p>

<div class=)

100vw, 1536px” /></p>

<p><span data-preserver-spaces=) Gangster Alvin

Gangster Alvin 100vw, 1229px” /></p>

<div class=)

100vw, 1286px” /></p>

<p><span data-preserver-spaces=) This eerie image shows two men crafting a death mask around 1908, a practice rooted in honoring and preserving the features of the dead.

This eerie image shows two men crafting a death mask around 1908, a practice rooted in honoring and preserving the features of the dead.